If you are wondering why Dynamic Grading sounds so natural and unobtrusive, a big part of it is thanks to the inconspicuous Spectrum parameter. Learn why it’s there and how every dynamics tool could benefit from it, though hardly any feature an equivalent.

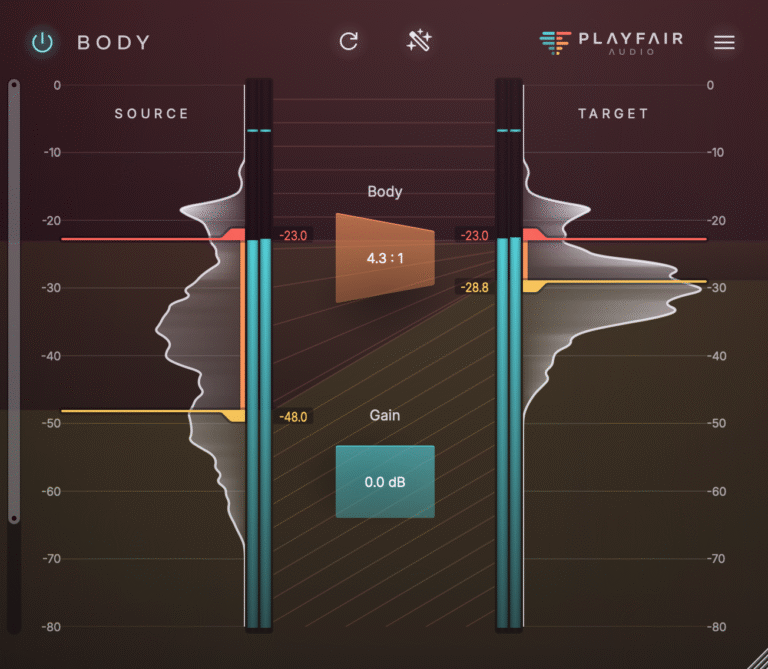

One piece of feedback I received over and over is that it “just sounds so good”. If you ask me for one single reason why that’s the case, it may surprise you that it’s not in Dynamic Grading’s most prominent feature, which is the threefold dynamic engine with its punch, body and floor ranges.

Now there are several details that are not obvious at first and which all together make this algorithm work so well. But by far the most important one is the Spectrum parameter. Without it, Dynamic Grading would just be a neat but hardly useful idea. But even more so, I’m convinced that most other dynamic processor designs could be improved by an order of magnitude if a similar feature was added.

Let me explain why.

The World is Pink

An interesting feature of music, but also of basically any other reasonably complex sound we hear in nature, is its spectral decay. Curiously, we perceive a music or other sound recordings as “balanced” in terms of low vs. high frequencies when the power at different frequencies decays at roughly 3 dB per octave towards higher frequencies, give or take. Pink noise has the same decay, so let’s call this more generally a “pink spectrum”. On the other hand, a spectrum with constant power over frequencies we call “white”.

Human hearing is tuned approximately for such a spectral decay. It would lead too far to explain this in detail, but it has to do with the constant relative bandwidth of filters. Let’s just say for now, that when you listen to pink noise, the “frequency sensors” in your ears are excited more or less uniformly (not exactly, but exactly enough). It’s also how realtime analyzers typically work, which is why they show a straight line when feeding them pink noise.

At the risk of going on a too huge tangent here, that’s actually not a coincidence! We can think of music as the output of a complex system with fractal properties, like many things we can observe in nature. These complex fractal systems tend to produce something called “fractional brownian motion”, which exhibits a curious kind of long-term time dependence. In other words, these processes have a type of memory which can not be described mathematically by differentiation or integration, but something right in between. Neither are they just a simple sequence of random samples (like white noise). This is something that music has in common not only with natural soundscapes, but also phenomena like the severity of floods or the movement of prices in the stock market.

What did I say about tangents?

Why Does It Matter?

Ok, back to dynamic processing. If you look at the purpose of compressors etc. from first principles, it is this: measure the variations of short-term loudness (= dynamics) and change them in a meaningful way. The second part is quite easy, as we can simply apply a gain to make something louder or softer, no matter if the spectrum is white, pink or whatever. But what about the first part? The grim truth is that hardly any of the dynamic tools out there deal with real-world music signals adequately when assessing dynamics.

The classic design of compressors and similar tools just averages signal amplitude or power over some short time constant, weighting all frequencies equally. They expect to deal with white spectra. Now if in reality we are typically dealing with pink-ish spectra where low frequency content comes in with more power, the low frequencies will dominate the assessment of dynamics.

This realization lead to some designs featuring a highpass filter to compensate for the overweighting of low frequencies. However, such filters operate with a slope of 6 dB per octave or multiples thereof. So although it helps a bit, it’s impossible to get the weighting “right” this way. Even a full-featured EQ can hardly solve this, and if it can, it’s too many knobs to turn for something that should be simple. Another convoluted and overly involved way of dealing with this problem is multiband compressors. All because the available mathematical building blocks can’t conveniently represent reality.

Turns out however, when investing just a bit more mathematical inconvenience to get the spectral weighting right, results are spectacular!

Spectrum Parameter to the Rescue

Dynamic Grading’s “Spectrum” parameter solves this elegantly. It controls a tilt filter with variable slope between 0 and 6 dB per octave that compensates for the signal’s spectral decay so that it appears “white” to the loudness measurement. Yes it really is as simple as that.

Note that the default setting is for a pink spectrum, which from experience is pretty close to the optimum in most cases. There is some variation though, as some recordings have a tendency towards the darker or brighter side. I found most of the time, a value between 2 and 4 dB per octave works great. The Magic Eye display above the Spectrum slider helps finding a good value. If the Magic Eye curve looks level, you’ve found the right spot.

The effect is most pronounced for example on a drum bus. If you want to experience the difference between Dynamic Grading and the conventional approach, just turn the Spectrum slider all the way to the left after having set up a healthy amount of compression/expansion in the punch, body and floor ranges. This is what – with some exceptions – almost all compressors do. You’ll immediately notice how the relations between the kick, snare and hihat go completely out of whack.

Every dynamics processor you could think of would benefit from this simple one-knob approach to spectral weighting, yet only very few actually do.

If you haven’t tried out Dynamic Grading yet, this article might have whetted your appetite. Don’t hesitate to check out the free trial, and don’t forget to reach out to us if you have any comments, questions or suggestions!