When you listen to a polished record, watch a tightly mixed song, or hear a voiceover that sounds just right, there’s a good chance a compressor has been at work. Compression is now so deeply embedded in audio production that it’s hard to imagine a time without it. But like much of the technology we use daily in music, it has a surprisingly physical and industrial past.

The Origins in Broadcasting and Telephony

Compressors originated as problem-solvers. During the 1930s and 40s, as radio and telephone networks expanded, engineers needed a way to prevent signal overload and ensure intelligibility. Automatic gain control systems were developed to handle inconsistent levels, particularly in speech.

Large valve-based limiters helped radio engineers manage unpredictable dynamics in live broadcasts. These early designs were about maintaining clarity, not character.

The Valve Era: Control with Character

In the post-war years, demand grew for tools that could handle dynamics in music production. Valve compressors such as the RCA BA-6A and Gates Sta-Level, originally designed for broadcasting, were adapted for use in studios. These units were large, slow by today’s standards, and coloured the sound in noticeable ways. But this wasn’t a drawback. That saturation and smooth gain reduction became desirable.

The Fairchild 660 and 670 added a new level of precision and transparency to the concept. Their variable-mu design and excellent build quality made them a go-to choice for mastering and stereo mixing. Despite being over 60 years old, they’re still considered benchmark tools.

Solid State and New Standards

By the late 1960s, transistor-based designs started to replace valves. Solid-state technology enabled faster response times, smaller footprints, and reduced maintenance.

The UREI 1176 is one of the most recognised compressors from this period. It used FET technology to deliver a fast, punchy sound that engineers quickly embraced for drums and vocals. Its continuously variable attack and release controls offered more flexibility than earlier models.

The dbx 160 followed, introducing RMS detection and soft-knee compression in a compact format. It brought consistency and clarity to a wide range of instruments and remains a popular choice for live and studio work.

API also contributed to the shift with their discrete op-amp-based 525. Integrated into the 500 series, it brought punch and forwardness to dynamic control, fitting seamlessly into modular workflows.

Studio Mainstay

By the 1980s, compressors had become essential. VCA designs, particularly those built into consoles, offered clean, predictable control over large numbers of channels. The SSL bus compressor became a defining part of the sound of modern mix busses, appreciated for its ability to ‘glue’ elements together.

Producers also began using compressors creatively. Parallel compression enhanced energy and sustain. Sidechain compression introduced rhythmic interplay between elements. Compression was no longer just a corrective tool—it was part of the sonic fingerprint.

Software and the Visual Era

As digital audio workstations became the standard in the 1990s, hardware compressors were emulated in software. The first wave focused on replicating the sonic characteristics of analogue units. Later developments introduced new functionality.

Software compressors provided full recall, automation, and flexible routing. They made complex processing—such as multiband and frequency-dependent compression—more accessible. For the first time, dynamics could be visualised, not just heard. This shifted how users approached compression, moving from purely auditory decision-making to a hybrid of listening and seeing.

Compression Redefined: Dynamic Grading

Just when it seemed compression had been thoroughly explored, Dynamic Grading took a different approach. It reframes how we interact with dynamics by removing the conventional language of threshold, ratio, attack, and release.

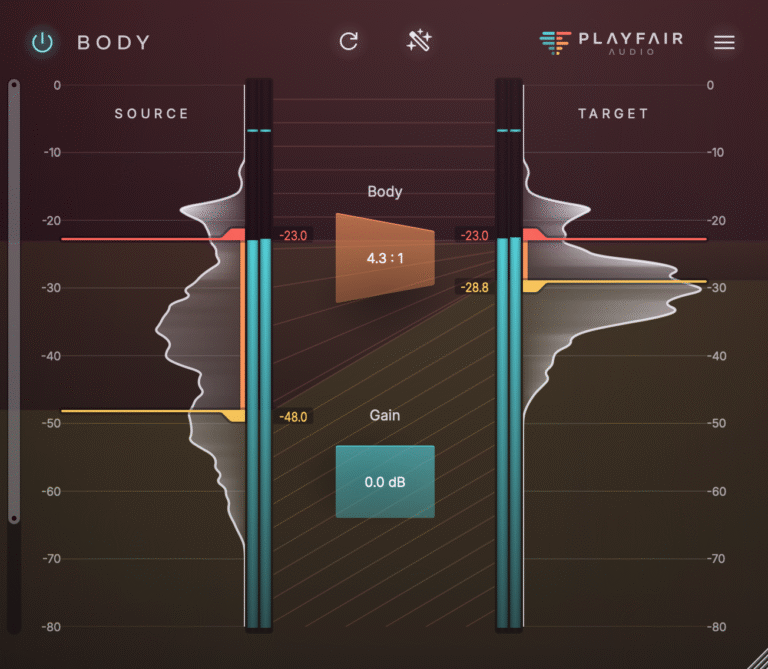

Instead, it presents a visual histogram of the signal’s dynamic content, allowing you to target and adjust three perceptual zones: Punch, Body, and Floor.

- Punch addresses transient information.

- Body focuses on the core of the signal.

- Floor captures subtle detail and decay.

Each can be compressed or expanded independently, offering precise control with immediate feedback.

This approach streamlines decision-making. You’re no longer translating between intention and abstract parameters. You work directly with what you hear and see, making adjustments in context.

Features like spectral weighting and auto-lookahead provide further nuance, while multichannel support ensures relevance in modern production environments. The result is a tool that feels natural and flexible, whether you’re tightening a bassline or shaping a full mix.

Dynamic Grading represents a shift from engineering tradition to perceptual design. It’s not an emulation. It’s a rethinking—built for how we work now. Download a copy now to try it. Perhaps the history of how you use a compressor is just about to enter a new chapter?