Transient designers are a staple in modern production. They are quick to use, easy to understand, and can be very effective in the right situation. Turn up attack, reduce sustain, move on with your day.

The trouble starts when we expect them to behave consistently across real world material.

Most classic transient designers are based on a relatively simple model. They detect fast level changes, split the signal into attack and sustain regions, then apply gain changes to each part. That approach works well on clean, isolated sounds. It is less dependable once you move into layered sources, dynamic performances, room ambience, or full mix elements.

One limitation is uniform treatment. Traditional transient shaping often applies the same processing behaviour regardless of how strong or weak each hit is. That can lead to results that feel uneven. Softer notes may become too forward, while stronger hits can become overly sharp or lose some of their natural body.

Another challenge is side effects. When attack is pushed hard, the tonal balance of a sound can shift in ways that are not always welcome. Engineers often find themselves trading punch against hardness, or clarity against weight.

There is also the question of context. Settings that sound right on a solo track may not translate when the rest of the mix is playing. Because many transient tools are purely reactive, they do not adapt much to changing signal conditions. That means more tweaking, more automation, and more compromise.

None of this makes transient designers bad tools. It simply shows the limits of a fixed attack and sustain model when dealing with complex dynamics.

Dynamic Grading And A More Structured View Of Dynamics

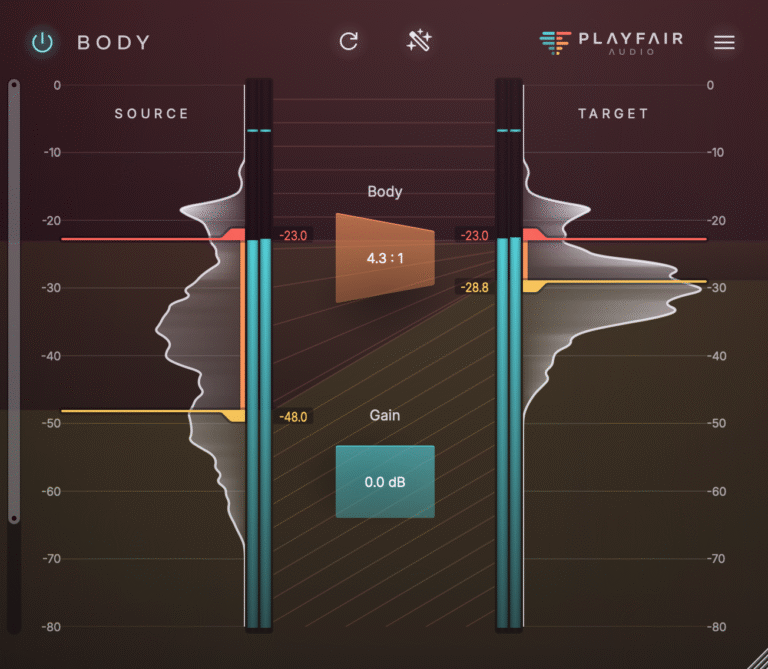

Dynamic Grading approaches the problem differently. Instead of only splitting sound into attack and sustain, it analyses the signal into multiple dynamic layers and lets you rebalance them directly.

That changes what “transient control” actually means in practice.

Take the Punch control. Rather than acting as a simple attack boost, Punch targets the impact component of a sound as its own dynamic layer. You can increase or reduce perceived impact without lifting everything that follows it. The result is often more punch without extra harshness, and more presence without added clutter.

Because the processing is adaptive, the response follows the material. Strong hits and subtle details are not forced through the same static curve. The relationship between impact and body stays more natural, even as you reshape it.

This becomes especially useful on sources that are not neatly separated. Drum buses, loops, acoustic recordings, and mixed material tend to respond in a more stable and predictable way. Instead of chasing a narrow sweet spot, you get a wider working range where adjustments stay musical.

Shaping Dynamics, Not Just Edges

Transient control is rarely just about the first few milliseconds. It is about how energy is distributed over time and how that energy supports the role a sound plays in the mix.

Dynamic Grading is designed around that broader view. Controls like Punch are part of a system that lets you rebalance dynamic structure, not just exaggerate the front edge of sounds. For many workflows, that leads to faster decisions and fewer tradeoffs between impact, tone and consistency.

Transient designers remain useful tools. Dynamic Grading simply extends the idea, giving you more precise ways to shape how sounds hit, breathe, and sit in the mix.